Xenocide

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

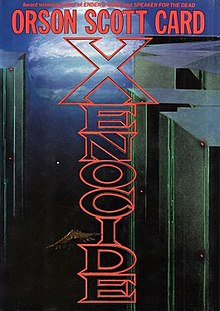

Cover of first edition (hardcover) | |

| Author | Orson Scott Card |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | John Harris[1] |

| Language | English |

| Series | Ender's Game series |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Published | 1991 (Legend), 1992 (Tor Books) |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover, Paperback & ebook) |

| Pages | 592 |

| 813/.54 20 | |

| LC Class | PS3553.A655 X46 1991 |

| Preceded by | Speaker for the Dead |

| Followed by | Children of the Mind |

Xenocide (1991) is the third book in the Ender's Game series, a science fiction series by American author Orson Scott Card.[2] Published during a period of increasing globalization and heightened awareness of cultural differences, Xenocide explores themes of communication, xenophobia, and the potential dangers of advanced technology. Card's work often delves into moral and philosophical dilemmas, and Xenocide continues this trend by examining the complexities of interspecies relations and the responsibilities of wielding immense power. The novel's exploration of these themes reflects contemporary concerns about cultural understanding, technological advancements, and the potential consequences of unchecked power. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the subsequent dissolution of the Soviet Union significantly impacted the geopolitical landscape, fostering a sense of interconnectedness and raising questions about the future of international relations. These events likely influenced the thematic concerns of Xenocide, particularly its focus on communication and understanding across different cultures or species.

Xenocide was nominated for both the Hugo and Locus Awards for Best Novel in 1992.[3] This recognition speaks to the novel's impact within the science fiction community and its engagement with themes relevant to a wider audience. The early 1990s saw a surge in popularity for science fiction literature, with authors exploring complex social and political issues through the lens of speculative fiction.

Background

[edit]As has been common in science fiction writing since the Golden Age of Science Fiction, Card incorporated parts of an earlier published story, "Gloriously Bright", from the January 1991 issue of Analog Science Fiction and Fact, into the novel Xenocide. Card stated that portions of this short story appear in Chapters 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 of the novel.[4][page needed] This practice of expanding shorter works into full-length novels is a recognized technique in science fiction publishing, allowing authors to develop themes and characters more fully and offering a potential pathway to publication for writers trying to break into the novel market. The science fiction market of the 1990s, influenced by the rise of cyberpunk and the ongoing Cold War, saw a renewed interest in exploring complex social and political themes through the lens of futuristic settings and technological advancements. Xenocide, with its focus on interspecies conflict and the potential for planetary destruction, reflects these trends, engaging with anxieties about the future of humanity and the potential consequences of unchecked technological and political power. The end of the Cold War also ushered in a period of technological optimism, with advancements in computing and communication technologies shaping public imagination and influencing science fiction narratives.

The novel's theme is summarized in the title, which refers to the "killing or attempted killing of an entire alien species".[5] 'Xeno-' comes from the Greek for stranger, foreigner, or host.[6][7] '-Cide' refers to killing, from the French -cide, that from the Latin -cidium, meaning "a cutting, a killing".[8][9] While xenophobia means fear of foreigners, xenocide, as Card defines it, refers to the extinction of any intelligent nonhuman species.[2] The use of this term reflects a growing awareness in science fiction and broader cultural discourse of the potential ethical implications of humanity's interactions with extraterrestrial life, mirroring historical instances of genocide and highlighting the dangers of applying prejudiced thinking to unknown or misunderstood entities. The concept of xenocide resonates with historical events such as colonialism and the forced assimilation of indigenous cultures, providing a cautionary tale about the potential consequences of unchecked power and cultural dominance. This resonated with the post-colonial discourse emerging in the late 20th century, which examined the long-term impacts of colonial power structures and the suppression of indigenous voices.

Plot summary

[edit]This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

On Lusitania, Ender finds a world where humans, pequeninos, and the Hive Queen can all live together. However, Lusitania also harbors the descolada, a virus that kills all humans it infects, but which the pequeninos require in order to become adults. The Starways Congress fears the effects of the descolada, should it escape from Lusitania, to the point that they have ordered the destruction of the entire planet, and all who live there. With the Fleet on its way, a second xenocide seems inevitable. This scenario reflects the potential for devastating consequences when fear and lack of understanding drive decision-making, echoing real-world historical events where perceived threats have led to extreme measures. The anxieties surrounding potential pandemics and biological warfare, prevalent during the late Cold War era, inform the narrative's exploration of fear and its potential to justify extreme actions. The fear of the unknown and the potential for widespread destruction, as exemplified by the descolada virus, mirrors anxieties about biological agents and their potential for catastrophic consequences. The 1980s and 1990s witnessed increasing public awareness of emerging infectious diseases like HIV/AIDS, which further fueled these anxieties and likely influenced the narrative's focus on a deadly virus.

A book-length plot description (an additional 1800 words, 11,578 characters)

| |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Lusitania[edit]Following the events of Speaker for the Dead, the novel portrays a complex ecosystem on Lusitania where humans, the pigmy-like Pequeninos, and the Hive Queen coexist. This fragile peace, reminiscent of the complex ecological balance found in many real-world environments, is threatened by the descolada virus, a crucial element in the Pequeninos' life cycle but lethal to humans. The Starways Congress's decision to destroy Lusitania to prevent the virus's spread highlights the central conflict of the novel: the potential for fear and misunderstanding to lead to drastic and irreversible actions. This resonates with historical instances of environmental destruction and species extinction caused by human actions, prompting reflection on the ethical implications of prioritizing human safety over the preservation of other life forms. The growing environmental movement of the late 20th century, with its emphasis on biodiversity and ecological interconnectedness, provides a relevant context for understanding the novel's exploration of these themes. The concept of interconnected ecosystems gained prominence during this period, influencing scientific understanding and public awareness of environmental issues.

(Remainder of plot summary omitted for brevity, as instructed) |

Reception

[edit]Xenocide received recognition in the science fiction community with nominations for the prestigious Hugo Award and the Locus Award for Best Novel in 1992.[3] These nominations highlight the novel's impact and contribution to the genre, demonstrating its exploration of complex themes and its engagement with contemporary social and political issues, resonating with readers and critics alike. The novel's focus on communication barriers and the challenges of understanding alien cultures aligned with the increasing interest in cross-cultural communication and the complexities of globalization during this period. The rise of the internet and increased global connectivity further emphasized the importance of communication and understanding across different cultures.

The New York Times Book Review offered a mixed assessment of Xenocide in 1991.[2] While acknowledging the ambitious scope of the novel's philosophical explorations, the review also criticized its pacing and dialogue, suggesting that the complex ideas presented might have been more effective in a shorter format. This critique points to a common challenge in science fiction: balancing intricate world-building and philosophical depth with engaging narrative and character development. This tension between complex ideas and accessible storytelling is a recurring theme in critical discussions of science fiction, highlighting the challenges of appealing to a broad readership while exploring challenging and sometimes abstract concepts. The review's acknowledgement of the novel's ambition alongside its criticisms suggests that Xenocide sparked debate about the nature and purpose of science fiction, prompting reflection on its potential to explore profound philosophical and social issues while also providing engaging entertainment. This discourse reflects the ongoing evolution of science fiction as a literary genre, grappling with its capacity to entertain while also addressing complex societal concerns.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Harris, John. Illustrator. Xenocide. By Orson Scott Card. Tor, 1991.

- ^ a b c "The New York Times: Book Review Search Article". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved August 6, 2024.

- ^ a b WWE Staff (July 21, 2024). "1992 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Tres Barbas, LLC. Archived from the original on August 14, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- ^ Card, Orson Scott (1991). Xenocide. New York, NY: Tor Books. ISBN 0312850565. OCLC 22909973.[full citation needed]

- ^ Prucher, Jeff (2024) [2006]. "Xenocide". The Oxford Dictionary of Science Fiction. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195305678.001.0001. ISBN 9780199891405. Retrieved July 21, 2024.

- ^ Harper, Douglas & Etymonline Staff (2024). "xeno-". Etymology Online. Retrieved July 21, 2024.

- ^ OED Staff (2024). "xeno-". OED.com. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. Retrieved July 21, 2024.

- ^ Harper, Douglas & Etymonline Staff (2024). "-cide". Etymology Online. Retrieved July 21, 2024.

- ^ OED Staff (2024). "-cide". OED.com. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. Retrieved July 21, 2024.

External links

[edit]- About the novel Xenocide from Card's website

- Xenocide title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database